Sep 1, 2023

Lovers' Dilemma Part I. Or an Iterated Game of Lovers as Great Filter

by Vengi

Collect this piece on Mirror

One day I was laying in the grass with a book and listening to psychedelic pop songs, as one does on an improbably sunny spring day in the Pacific North West. A song came on that I had heard many times before, each time imagining these hidden feelings between individuals, prospective lovers. Certainly because I was reading The Evolution of Cooperation (Axelrod, 1984) and daydreaming about Great Filters at the time, I imagined this unseen love existing between all individuals, a love lost across the entire human population, turning a sad song into an epic tragedy of societal discoordination.

The Great Filter [1] refers to these required filters, or barriers to development, that biological organisms must pass through as they exist over time, in order to survive and/or become more complex. Life needs the right star system, single cell assemblages before it can go multicellular, all the way to tools, technology, and who knows what other filters may emerge in the future. The Great Filter being the one that blocks civilizations from becoming interplanetary/stellar/galactic. Sociobiologically, for us here and now, I began thinking that the endless zero-sum competition represents our nearest barrier to development as a species, the highest probability catalyst to not surviving past the Great Filter. To me, learning how to cooperate better would seem the foundational next step required for humans to survive beyond these circumstances. My proposition would not be that we need to eliminate competition, competition is indeed necessary. Rather I propose that we need to greatly modulate and incentivize toward more cooperation if we are indeed all gonna make it (to a Kardashev Level I civilization).

The song was "The Way I Feel Inside"

Written by Rod Argent, 1964

Performed by The Zombies

Lyrics:

Should I try to hide

The way I feel inside

My heart for you?

Would you say that you

Would try to love me too?

In your mind

Could you ever be

Really close to me?

I can tell the way you smile

If I feel that I

Could be certain then

I would say the things I want to say tonight

But 'til I can see

That you'd really care for me

I will dream

That someday you'll be

Really close to me

I can tell the way you smile

If I feel that I

Could be certain then

I would say the things I want to say tonight

But 'til I can see

That you'd really care for me

I'll keep trying to hide

The way I feel inside

It's a sad song of an unshared love, an unseen love with no chance of reciprocity. An impossible love. Going around and around hoping for someone else to open up first, so that they may finally be able to reveal the way they feel inside.

Lovers' Dilemma

It's clear songwriter (and keyboardist!) Rod Argent wasn't thinking in game theoretical terms, but it's a rather elegant and romantic portrayal of the Prisoners' Dilemma, the lovers imprisoned by their own fear of vulnerability in being the first to reveal their feelings, aka 'cooperate'.

Game Theory, and more specifically Axelrod's Cooperation Theory, elucidates many possible enhancements to cooperative probabilities. If we know the rules of the game and strategies of the players, we can both predict the probabilistic outcome of future interactions as well as derive alternative strategies to improve outcomes. By quantifying subjective incentives, we are able to simulate games and strategies over time. We can even look at the game itself, to design better paths to emergent cooperative behavior. So let us fork the Prisoner's Dilemma to define and play through a new game, The Lovers' Dilemma.

Proposition:

Can we use game theory to derive a strategy to help the protagonist increase probability that they will find mutual love?

The Protagonist's Strategy

Let's start by deriving the strategy of this song's protagonist. The song doesn't stop at a single instance of the prisoners' dilemma, and actually extrapolates well into an iterated prisoners' dilemma, revealing their true strategy over time.

But 'til I can see

That you’d really care for me

I’ll keep trying to hide

The way I feel inside

The protagonist admits 'But 'til I can see', 'I'll keep trying to hide', so we can assume they plan on hiding their feelings upon first meeting someone new, and repeating that unless the other shares their feelings, in which case they'd cooperate and share their feelings too. In theory, but will we ever actually see this reciprocity of love?

The protagonist's strategy can be simplified to DEFECT-FIRST by hiding their feelings, then RECIPROCATE, copying the other's moves from then on.

- 1: DEFECT FIRST: hide feelings

- 2: RECIPROCATE: copy last move IF the other shares feelings: THEN share feelings ELSE hide feelings

- 3: ...

For sake of repetition let's label the strategy 'DOPYCAT', like 'copycat' but Defect-first. Defect-first strategies are oft referred to as 'mean'.

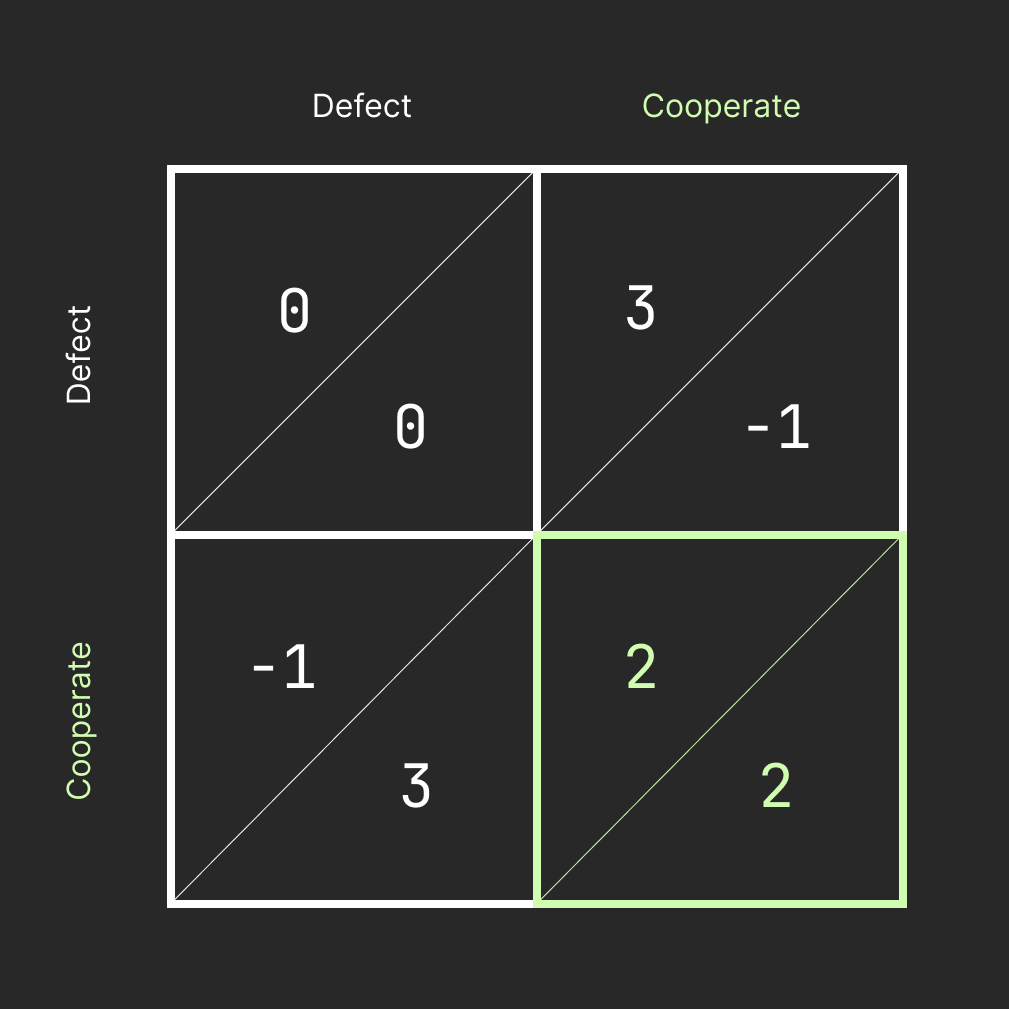

Payoff Matrix

Next, let's format a payoff matrix to play this love song out and see how different strategies perform over time. The exact values aren't all that important, it's the relationship between them that is the main thing to capture. By approximating the relationship between temptation, rewards, punishment, and sucker's payoff, we can run simulations, evaluating strategies against one another.

The Payoffs, or Approximate Quantitative Relationship Between Temptation and Rewards of Defection and Coopoeration respectively

To keep the incentives balanced as a true dilemma, our payoffs should borrow this relational schema from The Prisoners’ Dilemma:

T > R > P > S

T = 3 = Temptation to hide feelings (DEFECT)

R = 2 = Probable reward from sharing feelings (COOPERATE)

P = 0 = Punishment if neither shares (DEFECT)

S = -1 = Sucker's payoff for sharing alone (COOPERATE) Note: in this particular example, one can be hurt if sharing alone so payoff should reflect that as a negative.

The relationship of R > P implies that mutual cooperation is more beneficial than mutual defection, while the payoff relationships of T > R and P > S imply that defection is the dominant strategy for both players.

For cooperation to be profitable, that is more rewarding than defection, the reward should be greater than half the combined payoffs of the temptation to defect and the sucker's payoff.

R > (S+T)/2

The payoff matrix:

Possible outcomes:

-

Both Defect, no one shares No one gets hurt, but no gains either

0 + 0 for 0 points -

One shares feeelings, other hides

one might get a confidence boost, the other a loss in confidence

3 + -1 for 2 shared points -

Both share feelings

feelings are shared, thus can be reciprocated, and recognized as 'mutual love', an outcome that matches purpose.

2 + 2 for 4 points

Mutual Love => Supermodularity => Positive Sum Value

The preferred outcome here is obviously to get both lovers to open up, despite the threat of punishment and reward for staying closed off. Let's connect many interactions together into an iterated game in order to simulate and see how strategies can play out over time. We can also pull some strategies out of other songs for advice. We can use this info to surface ways to encourage higher probabilities of cooperation, and ultimately more positive sum value creation, aka Mutual Love in our Lovers' Dilemma.

As players unaware of our opponent's strategy, we tend to project our own strategies on others to simplify the computation of our own strategy. So extra discoordination emerges in the likelihood/perception that both players are using DEFECT-first ('mean') strategies (hiding their feelings). This means that even if they both plan to reciprocate feelings, there is actually zero probability of this ever happening, as we’ll see in the following Game #1.

Lovers' Dilemma Game #1: DOPYCAT v DOPYCAT

First let's assume both lovers were using this DOPYCAT strategy of DEFECT FIRST, then RECIPROCATE.

Move 1

Protagonist: Hide Feelings => DEFECT (1)

Other: Hide Feelings => DEFECT (1)

Move 2 (if there is another interaction)

Protagonist: RECIPROCATE -> DEFECT (1): hide feelings

Other: RECIPROCATE -> DEFECT (1): hide feelings

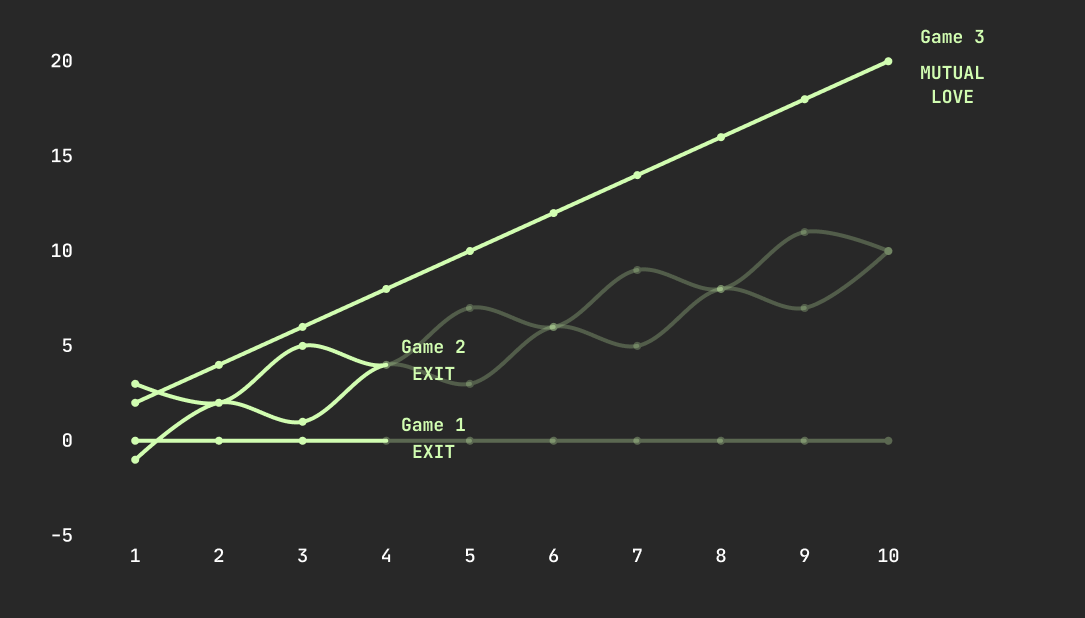

Extrapolating over 10 interactions (Fig A), we can see they wouldn't get very far. Clearly, this relationship hasn't much a chance of going anywhere at all. An inevitable result of a never ending silence of secrets, an absolute drain of attention for all involved.

Fig. A: Lovers' Dilemma Game #1: payoffs over 10 interactions

| Move | P1 | P2 | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ... | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Well maybe no one was hurt, but no feelings were ever shared either, so no love was gained between these two. It's likely that, in every following interaction, they will both simply reciprocate the previous perceived behavior by continuing to hide their feelings, until they exit the interaction completely to find another Lover's Dilemma.

An implication here is that there is a dependency of running into someone using a COOPERATE-first strategy for there to be a non-zero probability of actually sharing feelings. Gruesome, but perhaps reflective of today's game state. This also reveals how easily using a Defect-first strategy can endogenously reinforce itself as the dominant strategy over time. This can lead to a game pervaded by only defection, an ‘ALL-D’ game, where no one is really sharing truthful information and cooperation can actually become dormant and near extinction [2].

Introducing a Nice Strategy

In Game Theory, strategies that cooperate first are referred to as being 'nice'. Nice strategies actually tend to be rather robust strategies for fostering reciprocal cooperation, and thus positive sum value creation (in the case of the song, the warm feeling of mutual love, clearer a higher reward than just occasionally hearing that someone likes you). Strategies that are too forgiving, however, can get drained by more adversarial strategies. The most robust of 'nice' strategies found in Axelrod's Tournament, a tournament of computer programs simulating various strategies over time, was TIT FOR TAT [3]. It's robustness came from its ability to locate other cooperators (COOPERATE first) as well as defectors, sensing and responding to threats of defection through reciprocity. TIT FOR TAT is a silly name, so here, I'm opting to use a more descriptive label of 'COOPYCAT'. Like a 'copycat' that cooperates first and then reciprocates, copying the other's previous action.

COOPYCAT STRATEGY

Move 1. COOPERATE first

Always attempt cooperation first on interaction with a new agent.

Move 2. RECIPROCATE other player's last action.

If other player Defected, RESPOND with Defection.

IF other player Cooperated, RESPOND with Cooperation.

Now let's introduce someone with this strategy.

Lovers' Dilemma Game #2: DOPYCAT v COOPYCAT

Move 1

Protagonist: DEFECT (3): hides feelings

Other: COOPERATE (-1): shares feelings

Move 2 (if there even is another interaction)

Protagonist: RECIPROCATE -> COOPERATE (-1): shares feelings

Other: RECIPROCATE -> DEFECT (3): hides feelings

Move 3 (if there is another interaction)

Protagonist: RECIPROCATE -> DEFECT (3): hides feelings

Other: RECIPROCATE -> COOPERATE (-1): shares feelings

Extrapolated over 10 moves (Fig. B), we can see the cooperator helped them get a bit further, but it's extremely unlikely for interactions to continue long enough for any stronger feelings to grow. Depending on the lovers' respective forgiveness parameterizations, they'll likely opt to try elsewhere after one or two defections. The asymmetric reciprocity clearly leads to poor communication, mixed signals, and inevitable discoordination.

| Move | P1 | P2 | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | -1 | 2 |

| 2 | -1 | 3 | 2 |

| ... | 3 | -1 | 2 |

| ... | -1 | 3 | 2 |

| 9 | 3 | -1 | 2 |

| 10 | -1 | 3 | 2 |

| Totals | 10 | 10 | 20 |

Fig. B: Lovers' Dilemma Game #2: payoffs over 10 interactions

The assymetric reciprocity may lead to some low level feelings being shared, but it's extremely unlikely for interactions to continue long enough for any stronger feelings to grow, with constant exchange of mixed signals and punishments. Depending on the lovers' respective forgiveness parameterization, they'll likely opt to try elsewhere after one or two defections.

The ending verse of Wish You Were Here by Pink Floyd expresses this nicely:

We're just two lost souls swimming in a fishbowl, year after year

Running over the same old ground

What have we found?

The same old fears

Wish you were here

Lovers' Dilemma Game #3: COOPYCAT v COOPYCAT

Let's revisit our opening proposition:

Proposition: Can we use game theory to derive a strategy to help the protagonist increase probability that they find mutual love?

Let's give the protagonist some advice to cooperate first also and see how that goes. If we replay the interactions between them again, but replace both lovers’ strategies with COOPYCAT, we generate the following results (Fig. C).

Move 1

Protagonist: COOPERATE (2): Share feelings

Other: COOPERATE (2): Share feelings

Move 2

Protagonist: RECIPROCATE: COOP: (2): Share feelings

Other: RECIPROCATE: COOP: (2): Share feelings

Move 3

Protagonist: ...

Other: ...

| M | P1 | P2 | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| ... | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Totals | 20 | 20 | 40 |

Fig. C: Lovers' Dilemma Game #3: payoffs over 10 interactions

Now we're talking. By opting to share feelings first, the prospective lovers are able to check for and validate reciprocated feelings. With each mutual validation, the probability (p) and weighted value of next cooperation (w) intensifies, thereby increasing the likelihood and incentive to continue interacting. If a nice strategy can recognize other nice strategies, the probability of establishing supermodularity and manifesting positive sum value creation goes way up.

At Last performed by Etta James, written by Mack Gordon and Harry Warren:

I found a dream, that I could speak to

A dream that I can call my own

I found a thrill to press my cheek to

A thrill that I have never known

Benji Hughes also advocates strongly for a COOPERATE-first strategy in Waiting for an Invitation

If you're waiting for an invitation

You're gonna wait a long time

Wait a long time, wait a long time

If you're looking for an invitation

It's never gonna come, it's never gonna come

You're never gonna get one

Here, Hughes also hits on how complexity can thwart cooperation.

Lovers they try, they try to whip the stars into compliance

Careful, don't you pull too hard

Don't want to knock the planets out of alignment

Complex strategies can raise the probability of miscommunication through the sheer increase in possible behaviors to decipher, requiring more computation. This also feeds back into the other's behavior, creating two lost souls in a fishbowl once again.

Applicable Conclusions

1. Be Nice! (COOPERATE-first)

Mean (Defect-First) strategies carry the potential of a zero probability of cooperation.

Nice (Cooperate-first) always enables cooperators the ability to mutually recognize one another. Thus, Nice strategies are shown to greatly increase the likelihood of emergent incentives that support continuous cooperation.

Reciprocated cooperation is the main driver of positive sum value creation, aka Mutual Love in the Lovers’ Dilemma.

Players in Games 1 & 2 are likely to exit after 2 defections. Meanwhile, cooperators continue their supermodularity toward mutual love.

Players in Games 1 & 2 are likely to exit after 2 defections. Meanwhile, cooperators continue their supermodularity toward mutual love.

2. Forgive, but don't Forget (RECIPROCATE!)

The ability to sense and reciprocate both cooperation and defection is key.

As shown in Lovers' Dilemma #2, not forgiving at all and endlessly reciprocating ends in a standoff of defecting. At times, it could just be miscommunications and misunderstandings, and a little forgiveness could be used to reset one's strategy to Cooperate-first again when caught in a loop of defections. If they indeed update their strategy to cooperation as well, we can sense and reciprocate that cooperation. Games involving continuous defections, however, should be exited entirely, in order to find, or build, a more suitably cooperative environment.

3. MetaGame: Play the Game outside the Game

Choose to play with players with a high likelihood of using nice strategies over mean ones, as well as games with a high probability of pulling in and rewarding nice strategies over mean ones.

We can also look at the game outside the game, to design environments and mechanisms that address individual variables, that can feed back into each other for exponential enhancements.

- raise ability to sense/respond to cooperation

- raise ability to sense/respond to defection

Clarity on what constitutes a cooperation and/or defection raises ability for recognition. Responses also need to be recognizable in order to be effective, so clear, transparent values and communication can help to avoid mixed signals.

- raise probability (p) of repeat interactions

- raise weight (w), or importance, of future interactions

The probability and perceived value of repeat interactions in the future raises the importance of one's interactions today, which can elicit more cooperative behavior. Likewise, the importance perceived in an interaction today can raise probability of repeat interactions in the future.

From Game Theory to Cooperation Theory, into Complex Systems and Ecologies, into Cooperative Network Ecologies

Though perhaps a whimsical take on game theory, this piece has been but a tiny quantum emergence along a meandering path, searching for first principles of sustainably cooperative complex network systems, or cooperative network ecologies. The idea is to actively learn; to share perspectives as they're gained, and iterating alongside that acquisition of knowledge in the open, so as to maximize its plurality. I'm beginning with a transdisciplinary approach, sifting through many domains of knowledge to derive various mechanisms of coordination and cooperation throughout, no matter how primitive. The more primitive the better, in fact, as these may prove to be some of the most fundamental, interoperable, and ultimately valuable inputs into a mechanistic design toward Mutually Assured Cooperation.

A game is said to have rules and thus a structure, only if players are actively choosing to play the game. The playing of the game is the approval of the game's bounds.

– James P Carse Finite and Infinite Games

– Vengi

Footnotes and Further Reading

[1] The Great Filter

Orginal (revised) paper by Robert Hanson: http://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/greatfilter.html

Don't Fear the Filter as Scott Alexander's response from 2014: https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/05/28/dont-fear-the-filter/

[2] Cooperation Theory:

Evolution of Cooperation (Axelrod, 1984)

Complexity of Trust (Axelrod, 1997)

There are of course many variables that go into fostering long-term cooperation beyond this excerpt's scope and still even beyond the scope of Game Theory, the Prisoners' Dilemma, and Cooperation theory.

From Axelrod's Six Advances in Cooperation Theory 2000: https://www-personal.umich.edu/~axe/research/SixAdvances.pdf

Game theory allows a very rich way of analyzing what will happen in a specific strategic context. To specify a game, one needs to specify the players, the choices, the outcomes as determined jointly by the choices, and the payoffs to the players associated with the outcomes. ... The rationality assumption of traditional game theory has been widely challenged. Among the leaders of the challenge is Herbert Simon (1982), who has emphasized that people have limited knowledge of their situations, limited ability to process information, and limited time to make choices. ... Cooperation Theory has taken these observations seriously, and is as likely to study adaptive actors as it is to study fully rational actors. It should be noted that in recent years, game theory as a whole has begun to relax the assumption of rational actors, and studied various forms of adaptive behavior (Samuelson 1997, Hofbauer and Sigmund 1998, Fudenberg and Levine 1998, Young 1998). The emphasis on adaptive actors and evolutionary processes that has characterized Cooperation Theory from the beginning is now becoming quite widespread throughout game theory.

– Axelrod

[3] Evolution of Trust (Case, 2014)

There are many more deep insights to be found throughout the decades of research done in Game Theory and further into Cooperation Theory. I highly recommend the interactive and visceral The Evolution of Trust by Nicky Case. It's based on Axelrod's The Evolution of Cooperation and its sequel Complexity of Cooperation and does a remarkable job of elucidating the evolutionary effects of strategies over time, where the entire game dynamic changes and whole populations of strategies can die out through selection or emerge through mutation, similar to complex biological systems.